What is shape analysis?

a brief introduction to the geometry of shape warping

In school, we’re taught how Pythagoras’ theorem can be used to compute the distance between points in Euclidean space. The straight line segment connecting two points is the simplest example of a geodesic curve – an optimal path that connects one point with another. But how do you compute optimal warps that deform geometric shapes into one another? And what exactly does optimal mean?

We all have an intuition for similarity between shapes. Perhaps you agree that a right-angled triangle resembles an equilateral triangle more than a circle (or perhaps you don’t).

Whether so mathematically depends on the definition of distance between shapes. Indeed, in mathematics the concept of distance is abstract and goes well beyond Euclidean space. Thus, two shapes are similar if the distance between them is small. But we have to be careful: there’s no canonically given shape distance. What is suitable depends on the application. The mathematical theory of shape analysis is flexible enough to allow many choices, yet rigid enough to admit a unified framework for analysis and numerical computations.

Historical overview

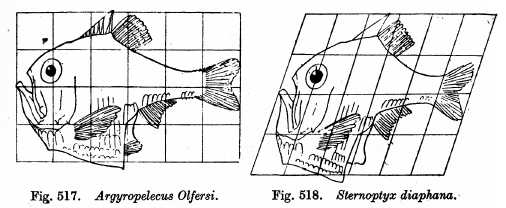

The rich mathematical foundation of shape analysis springs from its history. The genesis can be found in painter and theorist Albrecht Dürer’s Vier Bücher von Menschlicher Proportion from 1528, and, much later, in D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s influential 1917 book On Growth and Form

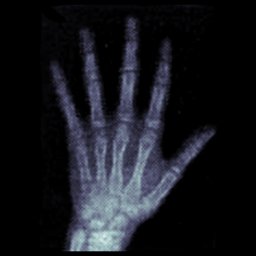

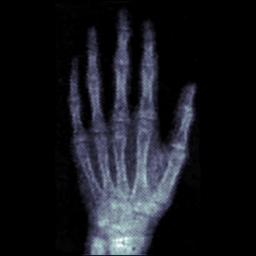

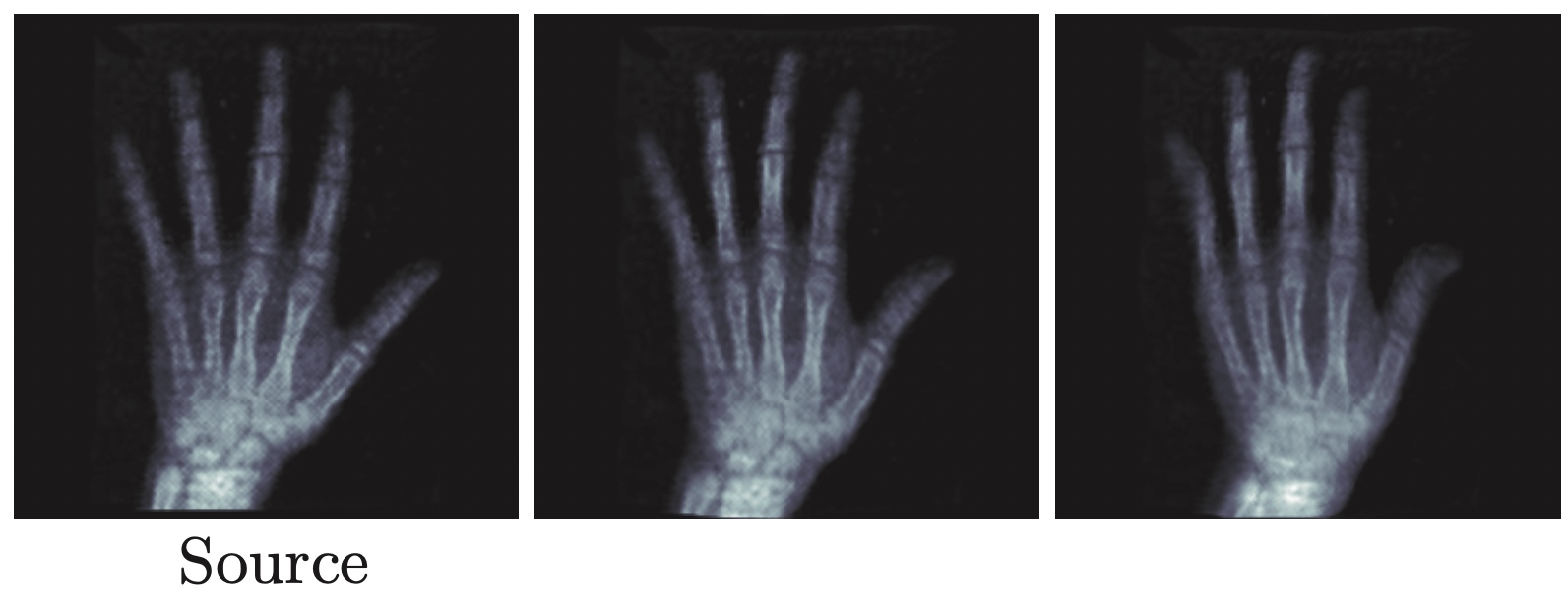

During the 1990’s, together with biomechanical engineer Michael Miller at John Hopkins University, Grenander applied the deformable template framework to variability in human anatomy. The need for such a model, and by extension the birth of computational anatomy, was a direct consequence of the increased availability of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and other medical imaging techniques.

The mathematical leap by Grenander and Miller was an infinite-dimensional setting, with \(G\) as a group of diffeomorphisms acting on a template 3-D image of, for example, the brain. The continued mathematical developments were influenced by a series of events.

In the spring of 1997, Grenander and Miller presented their work in a symposium celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Division of Applied Mathematics at Brown. David Mumford, colleague and friend of Grenander, organized the symposium. Another breakthrough then came about. It was understood that computational anatomy is closely tied to topological hydrodynamics - the theory of geodesic equations on groups of diffeomorphisms, initiated by Vladimir Arnold’s 1966 discovery that the incompressible Euler equation is a (reduced) geodesic equation on volume preserving diffeomorphisms

By the year 2000, computational anatomy was thereby established at Brown, John Hopkins, and ENS-Cachan. Via Jerrold Marsden at Caltech it also began to appear in contexts of geometric mechanics

As a next event, Sarang Joshi, student of Miller at the time, was working with a model where diffeomorphisms act on landmark points. Following a 2002 meeting on image analysis at Los Alamos National Laboratory, Miller discussed Joshi’s model with Darryl Holm, in particular its connection to soliton solutions in the Camassa-Holm shallow water equation. Through Marsden, Holm, and many collaborators, computational anatomy then quickly spread also in the geometric mechanics community.

From these and certainly also other events, the mathematical field of shape analysis took form.

Warps by geodesics

The starting point in shape analysis is a Riemannian manifold \(M\), usually compact. This is your spatial domain. To keep it simple, we continue here with \(M\) as the \(n\)-dimensional cube

\[M = \{ (x_1,\ldots,x_n)\mid x_k \in [0,1] \}\]equipped with periodic boundary conditions for each coordinate. (It is called the flat torus in geometry and is usually though of as the quotient space \(\mathbb{R}^n/\mathbb{Z}^n\)).

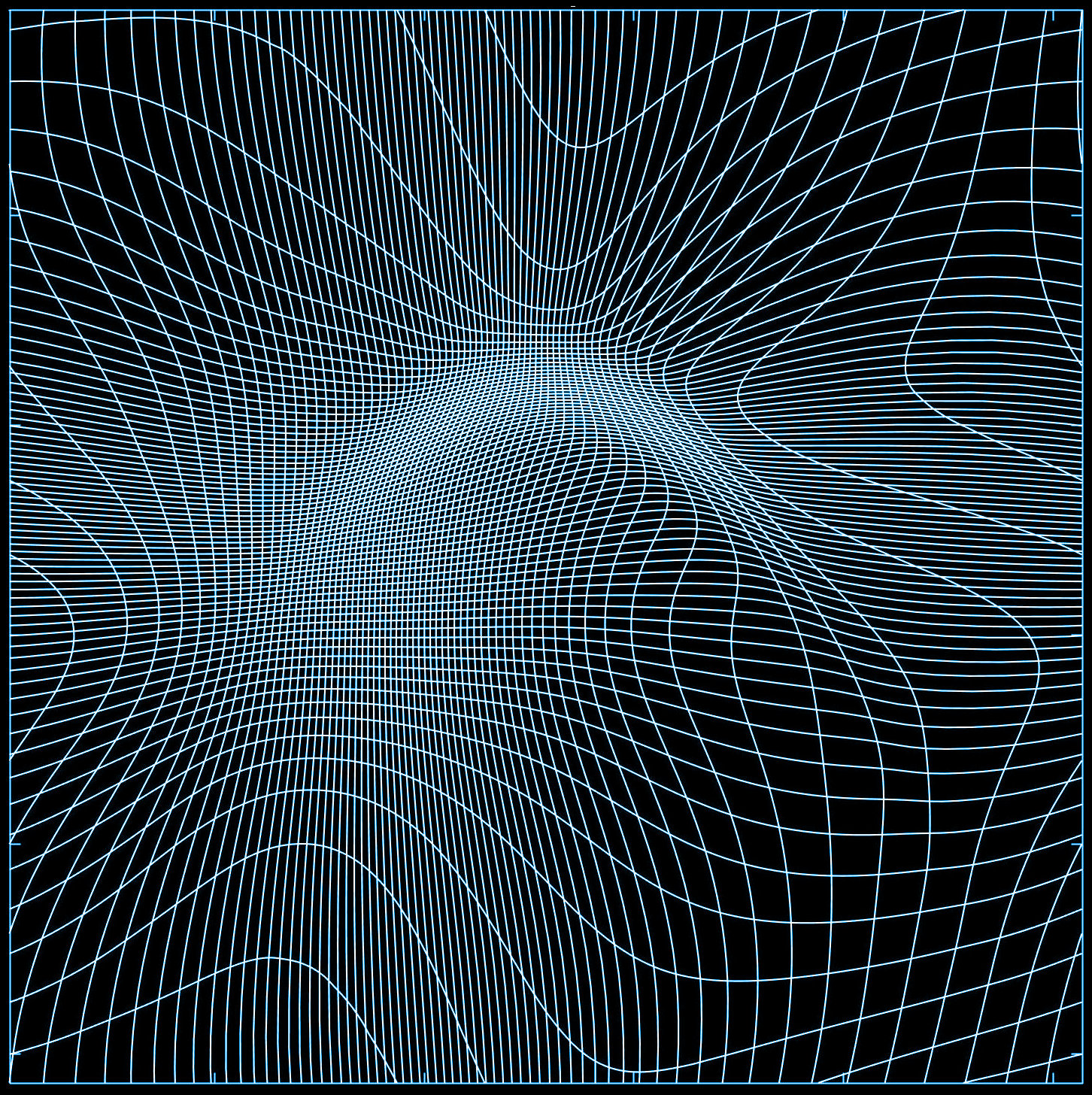

A diffeomorphism on \(M\) is a smooth, bijective map \(\varphi\colon M\to M\) whose inverse \(\varphi^{-1}\) is also smooth. Such a map deforms \(M\) but keeps its manifold structure intact. It’s helpful here to think of a uniform grid on \(M\) and then apply the map to each point on the gridlines to obtained a warped grid. If \(\varphi\) is a diffeomorphism, initially parallell gridlines cannot intersect or collide in the warped grid.

The warped grid is important in applications of shape analysis. We’ll return to it later, but first something about the mathematical structure of diffeomorphisms.

Lie group and Lie algebra

The set of all diffeomorphisms on \(M\) forms a group \(\operatorname{Diff}(M)\) with composition as group multiplication. Indeed, if \(\varphi\) and \(\eta\) are diffeomorphisms then \(\varphi\circ\eta\) is again a diffeomorphism. The group inversion is \(\varphi\mapsto\varphi^{-1}\). The group identity is the map \(\operatorname{id}\colon M\to M\) defined by \(\operatorname{id}(x) = x\). One should think of \(\operatorname{Diff}(M)\) as an infinite-dimensional Lie group. This notion is precise in the category of Fréchet Lie groups (cf. Kriegl and Michor

Take now a smooth path \(\gamma: [0,1] \to \operatorname{Diff}(M)\) such that \(\gamma(0) = \operatorname{id}\). It is useful to picture \(\gamma\) as a continuous warp. Indeed, we can interpret \(\gamma\) as a map \(\gamma:[0,1]\times M \to M\). A point \(x\in M\) is then continuously moved along the path \([0,1]\ni t\mapsto \gamma(t,x) \in M\). If we differentiate this path we obtain a vector

\[\frac{\partial \gamma(t,x)}{\partial t} \in T_{\gamma(t,x)} M \simeq \mathbb R^n.\]This vector depends smoothly on \(t\) and \(x\), but we can also think of it as a vector depending on \(t\) and the variable \(y \equiv \gamma(t,x)\). Since \(x = \gamma^{-1}(t,y)\) depends smoothly on \(y\), we thereby obtain a smooth map

\[(t,y) \mapsto v(t,y) \equiv \frac{\partial \gamma(\tau,\gamma^{-1}(t,y))}{\partial \tau}\Bigg|_{\tau=t} \in T_{y} M \simeq \mathbb R^n .\]If we now instead fix \(t\), then \(v(t,\cdot) \equiv v_t\) maps a point \(y\in M\) to a vector in \(T_{y}M\). Thus, \(v_t\) is a smooth, time-dependent vector field on \(M\). By construction, the path \(t\mapsto \gamma(t,x)\) is a solution to the non-autonomous ordinary differential equation

\[\frac{\partial\gamma(t,x)}{\partial t} = v\big(t,\gamma(t,x)\big).\]It can be written for all \(x\in M\) simultaneously if we again think of \(\gamma\) as a path on \(\operatorname{Diff}(M)\):

\begin{equation}\label{eq:ode} \dot\gamma = v_t \circ \gamma, \quad \gamma(0) = \operatorname{id} \end{equation}

where \(\dot\gamma\) denotes differentiation with respect to \(t\) (the notation originates from mechanics, where \(t\) is the time variable). Equation \eqref{eq:ode} captures a golden rule in shape analysis: warps are generated by integrating time-dependent vector fields.

If we return to the interpretation of \(\operatorname{Diff}(M)\) as a Lie group, our derivations show that its Lie algebra is the space of smooth vector fields \(\mathfrak{X}(M)\). The associated bracket

\[[\cdot,\cdot]\colon \mathfrak{X}(M)\times \mathfrak{X}(M) \to \mathfrak{X}(M)\]is the Jacobi-Lie bracket, which in vector calculus notation, with \(u\) and \(v\) as column vectors, is given by

\[[v,u] = \nabla u \cdot v - \nabla v\cdot u\]where “dot” denotes matrix multiplication and \(\nabla u\) is the elementwise gradient (geometrically it is the co-variant derivative).

Riemannian metric on the group

Our objective is to introduce a distance function on \(G=\operatorname{Diff}(M)\). In other words, a function \(d_G\colon G\times G \to \mathbb{R}\) that for all \(\varphi, \eta,\psi\in G\) fulfills

- vanishing distance to itself: \(d_G(\varphi,\varphi) = 0\)

- positivity: if \(\varphi \neq \eta\) then \(d_G(\varphi,\eta)> 0\)

- symmetry: \(d_G(\varphi,\eta) = d_G(\eta,\varphi)\)

- triangle inequality: \(d_G(\varphi,\psi) \leq d_G(\varphi,\eta) + d_G(\eta,\psi)\).

In addition, we would like the distance to respect the group structure in the following sense

- right invariance: \(d_G(\varphi,\eta) = d_G(\varphi\circ\psi,\eta\circ\psi)\).

The last property is not an absolute requirement, but is natural to have. It implies that \(d_G(\operatorname{id},\varphi) = d_G(\operatorname{id},\varphi^{-1})\) and \(d_G(\operatorname{id},\varphi\circ\psi) \leq d_G(\operatorname{id},\varphi) + d_G(\operatorname{id},\psi)\).

Once you have a distance function, you can measure the “length” of \(\varphi\in\operatorname{Diff}(M)\) as its distance to the identity \(d_G(\operatorname{id},\varphi)\). But we want more than that. We want, in addition, a continuous warp from \(\operatorname{id}\) to \(\varphi\). In other words, a smooth path \(\gamma\colon [0,1] \to \operatorname{Diff}(M)\) with \(\gamma(0)=\operatorname{id}\) and \(\gamma(1) = \varphi\). There is a way to do both things simultaneously and it spells Riemannian geometry. The notion goes back to Carl Friedrich Gauss and Bernhard Riemann and is today a major branch of geometry. Here is chiefly how it works:

A manifold \(Q\) admits tangent spaces and for each \(q\in Q\) its tangent space \(T_qQ\) is linear. If we assign to each tangent space an inner product \(\langle\cdot,\cdot\rangle_q\), then we can measure the length of a \(C^1\) curve segment \(\gamma\) in \(Q\) as

\begin{equation}\label{eq:length} \ell = \int_{t_0}^{t_1} \sqrt{\langle\dot\gamma(t),\dot\gamma(t)\rangle_{\gamma(t)}}\, dt \end{equation}

The length is independent of how we parameterize \(\gamma\) (prove this!), so it truly gives a length to \(\gamma\) as a curve. To obtain a distance function \(d_Q(q_0,q_1)\), find among all curve segments connecting \(q_0\) and \(q_1\) one that minimizes the length. This length is the distance and the corresponding curve segment is called a geodesic curve between \(q_0\) and \(q_1\). The distance function defined this way will automatically fulfill the four required properties listed above.

As you guessed, the aim is to equip \(\operatorname{Diff}(M)\) with a Riemannian metric \(\langle\cdot,\cdot\rangle_{\varphi}\) and thereby obtain a distance function \(d_G\). There’s still some work to do, however, because of the additional property of right invariance. Also, how does this Riemannian story connect to the golden rule in \eqref{eq:ode}? Mathematically we’re in the intersection between Lie theory and Riemannian geometry, which is overall an important theme is geometric mechanics with many interesting examples: rigid body motion, incompressible fluids, Heisenberg spin chain, Korteweg–De Vries (KdV) equation, Camassa-Holm equation, magneto-hydrodynamics, etc. (cf. Arnold and Khesin

Right invariance of \(d_G\) in the Riemannian case implies that the length of \(\gamma(t)\) must be the same as the length of \(\tilde\gamma(t) \equiv \gamma(t)\circ\eta\) for any \(\eta\in G\). Since \(\dot{\tilde\gamma}(t) = \dot\gamma(t)\circ\eta\), we conclude from the length formula \eqref{eq:length} that the Riemannian metric must fulfill

\[\langle\dot\gamma(t),\dot\gamma(t)\rangle_{\gamma(t)} = \langle\dot\gamma(t)\circ\eta,\dot\gamma(t)\circ\eta\rangle_{\gamma(t)\circ\eta}\]This formula relates the inner product at \(T_{\gamma(t)}G\) to the inner product at \(T_{\gamma(t)\circ\eta}G\). In fact, one is determined from the other. Since this should hold for any \(\eta\in G\), and since all elements in \(G\) can be reached by suitably selecting \(\eta\), it follows that a right invariant Riemannian metric is fully determined from only one inner product. Naturally, as the defining inner product for the right invariant Riemannian metric, we take the one at the identity tangent space \(T_{\operatorname{id}}G\), i.e., at the Lie algebra of \(G\). The formula for the length of \(\gamma\) then becomes

\[\ell = \int_{t_0}^{t_1} \sqrt{\langle\dot\gamma(t)\circ\gamma(t)^{-1},\dot\gamma(t)\circ\gamma(t)^{-1}\rangle_{\operatorname{id}}}\, dt\]Does this look familiar? The quantity \(\dot\gamma(t)\circ\gamma(t)^{-1}\) is the vector field \(v_t\) in the golden rule equation \eqref{eq:ode} above! Expressed differently, if \(\gamma(t)\) is generated by a time-dependent vector field \(v_t\) as in equation \eqref{eq:ode}, then the length of \(\gamma(t)\) with respect to a right invariant Riemannian metric is given by

\[\ell(v) = \int_{t_0}^{t_1} \sqrt{\langle v_t,v_t \rangle_{\operatorname{id}}}\, dt .\]A geodesic curve between \(\operatorname{id}\) and \(\varphi\) is thereby obtained by minimizing \(\ell(v_t)\) under the constraint that \(\gamma(t)\) generated by \(v_t\) according to \eqref{eq:ode} should fulfill \(\gamma(1)=\varphi\).

The only thing left to worry about is how to choose the inner product \(\langle \cdot,\cdot\rangle_{\operatorname{id}}\) on the Lie algebra \(\mathfrak{X}(M)\). As I already indicated, there is no canonical choice that always works: the choice is part of the particular shape model one is interested in. There is, however, one choice that at first seems natural, but which is not good: the \(L^2\) inner product on \(\mathfrak{X}(M)\). This choice doesn’t give a well-posed geodesic equation: infinite-dimensional complications pop up in the analysis since the corresponding norm is not strong enough. The standard choice is instead to use a higher-order Sobolev inner product, for example the \(H^k\) inner product

\[\langle v,v\rangle_{\operatorname{id}} = \int_M v (1-\Delta)^k v \, dx.\]For our purposes, it is convenient to keep things general and just assume that the inner product is of the form \(\langle v,v\rangle_{\operatorname{id}} = \langle v, Av\rangle_{L^2}\) for some self-adjoint, positive operator \(A\) (often referred to as an inertia operator, again borrowing from the language of geometric mechanics).

We now have everything we need to formulate the geodesic problem:

\[\min_{v\colon [0,1]\to \mathfrak{X}(M)} \int_0^1 \sqrt{\langle v_t, Av_t\rangle_{L^2}}\, dt\]under the constraints

\[\dot\gamma(t) = v_t\circ\gamma(t), \quad \gamma(0)=\operatorname{id}, \quad \gamma(1) = \varphi .\]Once \(v\) is found, the distance is given by

\[d_G(\operatorname{id},\varphi) = \ell(v).\](Since the distance is right invariant, it is enough to define it from the identity).

Connection to kinetic energy systems

The length functional \eqref{eq:length} in Riemannian geometry is a little bit cumbersome to work with. Partly because it contains a square root, and partly because it doesn’t provide a unique solution among parameterized curves \(\gamma(t)\) (any reparameterization gives another solution, remember). There is a beautiful resolution to this problem, which connects Riemannian geodesics to kinetic energy systems in mechanics. Such a system is defined by a Riemannian metric \(\langle \cdot,\cdot\rangle_{q}\) on a configuration manifold \(Q\). It describes a particle moving on \(Q\) with respect to the Lagrangian given by the Riemannian metric \(L(q,\dot q) = \frac{1}{2}\langle \dot q,\dot q\rangle_q\). The variational principle of mechanics states that \(\gamma(t)\) is a solution curve if, among all curves with fixed end-points \(\gamma(t_0)\) and \(\gamma(t_1)\), it extremizes the action functional

\[S(\gamma) = \int_{t_0}^{t_1} L\big(\gamma(t),\dot \gamma(t)\big) \, dt\] \[= \frac{1}{2} \int_{t_0}^{t_1} \langle \dot\gamma(t),\dot\gamma(t)\rangle_{\gamma(t)}\, dt .\]Lemma:

\(\gamma(t)\) is a solution curve to the mechanical system if and only if it is a geodesic curve (with respect to \(\langle \cdot,\cdot\rangle_{q})\), parameterized so that \(\frac{d}{dt}\langle\dot\gamma(t),\dot\gamma(t)\rangle_{\gamma(t)} = 0\).

Proof sketch:

The key is that if \(\gamma(t)\) is a mechanical solution curve, then the kinetic energy \(T(q,\dot q) = \frac{1}{2}\langle \dot q,\dot q\rangle_{q}\) is a first integral (prove this!). Take now a variation of \(\gamma(t)\), i.e., a map \((t,\epsilon)\to \tilde\gamma(t,\epsilon)\in Q\) such that \(\tilde\gamma(t,0) = \gamma(t)\). We first show that

Let’s calculate the right-most variation

\[\frac{d}{d\epsilon}\Bigg|_{\epsilon=0} \ell(\tilde\gamma_\epsilon) = \int_{t_0}^{t_1} \frac{1}{2}\frac{\frac{d}{d\epsilon}\langle \dot{\tilde\gamma}(t,\epsilon),\dot{\tilde\gamma}(t,\epsilon)\rangle_{\tilde\gamma(t,\epsilon)} }{\sqrt{\langle \dot\gamma(t),\dot\gamma(t)\rangle_{\gamma(t)}}}\] \[= \frac{t_1-t_0}{2 \sqrt{T(\gamma(0),\dot\gamma(0))}} \frac{d}{d\epsilon}\Bigg|_{\epsilon=0} S(\tilde\gamma_\epsilon)\]where in the last equality we use that \(T\) is conserved. Since \(\dot\gamma(0) \neq 0\) we get that \(T(\gamma(0),\dot\gamma(0)) > 0\) and so the result follows.

For the other direction, let \(\gamma(t)\) be a geodesic curve parameterized so that it has constant speed. This means exactly that \(T\) is conserved along \(\gamma(t)\). We now simply reverse the calculation above. QED.

Instead of solving the original geodesic minimization problem, we can now solve the corresponding kinetic energy variational problem, which is simpler (no square root) and also doesn’t have the re-parameterization degeneracy. Furthermore, once we’ve computed the curve \(\gamma(t)\) this way, its length is given simply by \(\ell(\gamma) = (t_1-t_0)\lVert \dot\gamma(0)\rVert_{\gamma(0)}\), where \(\lVert\cdot\rVert_q\) is the norm corresponding to \(\langle\cdot,\cdot\rangle_q\).

The geodesic–kinetic energy equivalence carries over to the right invariant geodesic problem on \(\operatorname{Diff}(M)\) formulated in terms of the vector field \(v_t\). Indeed, it can be reformulated as

\[\min_{v\colon [0,1]\to \mathfrak{X}(M)} \frac{1}{2}\int_0^1\langle v_t, Av_t\rangle_{L^2}\, dt\]under the constraints

\[\dot\gamma(t) = v_t\circ\gamma(t), \quad \gamma(0)=\operatorname{id}, \quad \gamma(1) = \varphi .\]The functional to be minimized is now quadratic in \(v\) and the distance function is given by

\begin{equation}\label{eq:energy_from_initial} d_G(\operatorname{id},\varphi) = \sqrt{\langle v_0,A v_0 \rangle_{L^2}} . \end{equation}

Geodesic shape matching

So far we’ve learned quite a bit about geodesics on diffeomorphisms, but little about shapes. First of all, what are shapes?

To answer this question we need to talk about group actions. A Lie group \(G\) is said to have a left action on another manifold \(S\) if there is a map \(\varrho\colon G\times S\to S\) that for any \(\varphi,\eta\in G\) and \(s\in S\) preserves left group multiplication

\[\varrho(\eta,\varrho(\varphi, s)) = \varrho(\eta\circ\varphi, s) .\]Usually the action map \(\varrho\) is left out in the notation and replaced by \(\varphi\cdot s \equiv \varrho(\varphi,s)\). The condition then looks almost like an associative law

\[\eta\cdot (\varphi \cdot s) = (\eta\circ\varphi)\cdot s .\]Now, in shape analysis, a shape space is any manifold \(S\), finite or infinite dimensional, upon which the group \(G=\operatorname{Diff}(M)\) acts. Here are some common examples:

-

Smooth functions \(C^\infty(M,\Omega)\) for some co-domain \(\Omega\subset \mathbb{R}^d\). The action is \(\varphi\cdot f = f\circ\varphi^{-1}\). Real valued functions with \(\Omega = [0,1]\) are usually thought of as “pre-discretized” gray-scale images. Color images (with red, green, blue channels) correspond to \(\Omega = [0,1]^3\).

-

Landmark space is \(M^d\), i.e., a tuple of \(d\) points in \(M\). The actions is \(\varphi\cdot (p_1,\ldots,p_d) = (\varphi^{-1}(p_1),\ldots, \varphi^{-1}(p_d))\). Normally it is required that all points \(p_1,\ldots,p_d\) are different from each other.

-

Immersions \(\mathbb{S}^1\to M\), i.e., closed, smooth curves \(\sigma(s)\) in \(M\). The action is \(\varphi\cdot \sigma = \varphi^{-1}\circ\sigma\).

-

Smooth probability density functions (PDFs) on \(M\). These are smooth, strictly positive functions \(C^\infty(M,\mathbb{R}_{>0})\) that fulfill \(\int_M \rho \, dx = 1\). The action is \(\varphi\cdot\rho = \rho\circ\varphi^{-1} \lvert D\varphi^{-1}\rvert\). Notice that this action preserves the normalization of \(\rho\) (prove this!).

Warping templates

Let now \(S\) be a shape space for \(G=\operatorname{Diff}(M)\). The idea of Grenander is to start from a template shape \(s_0 \in S\) and then deform it by applying a diffeomorphic warp \(\gamma(t)\). We then obtain a corresponding warp \(t\mapsto \gamma(t)\cdot s_0\) in \(S\). One can do all sorts of interesting things with such warps (why not random walks in shape space!). I’ll focus here on the matching problem, where there’s also a target shape \(s_1\in S\), and the objective is to find a warp \(\gamma(t)\) that deforms \(s_0\) to \(s_1\). Actually, this is not quite true; to require \(\gamma(1)\cdot s_0 = s_1\) is too rigid, for two reasons.

-

Typically not all elements in \(S\) can be reached by action on \(s_0\); only those on the orbit \(G\cdot s_0\) of \(s_0\). For example, if \(s_0 \in C^\infty(M,\mathbb{R})\) is generic (it’s a Morse function), then \(\varphi\cdot s_0\) preserves the number of critical points and their values: if \(x_c\) is a critical point of \(s_0\), then \(\varphi^{-1}(x_c)\) is a critical point of \(\varphi\cdot s_0\). Thus, a necessary requirement for \(s_1\) to belong to the same orbit as \(s_0\) is that it has the same number of critical points and the same set of critical values (cf. Morse homology). This is essentially never the case in applications.

There is actually a situation where the orbit consists of the entire shape space: probability density functions. Indeed, this is a result of Moser . The story of shape analysis in this case is extremely interesting: it leads to optimal mass transport. But that story is for another post. -

It is usually not desirable to get as “close as possible” to the target \(s_1\), since it would lead to an extremely complicated warp that is hard to resolve numerically. The aim is a nice enough warp that takes the template sufficiently close to the target.

Of course, “nice enough” and “sufficiently close” are not very rigorous statements. Let’s make mathematical sense of it.

We first introduce a distance function \(d_S\) on \(S\). This allows us to measure how close \(\varphi\cdot s_0\) is to the target \(s_1\). A typical example for functions, i.e., \(S=C^\infty(M,\mathbb{R})\), is to take the \(L^2\) norm.

Next, recall from above that we already have the Riemannian distance function \(d_G\) on the group. We then require the distance \(d_G(\operatorname{id},\varphi)\) to be not too large (this is the “niceness” of the warp). The basic matching problem in shape analysis is the following:

Find \(\varphi\in G\) that minimizes

$$ d_G(\operatorname{id},\varphi)^2 + \frac{1}{\sigma^2}d_S(\varphi\cdot s_0, s_1)^2 $$

where \(\sigma > 0\) is a parameter that balances regularity of the warp (first term) against similarity between the shapes (second term).

Now we take a leap by incorporating everything we’ve learned above about the Riemannian distance \(d_G\). Recall the golden rule: we want to generate diffeomorphisms via time-dependent vector fields. Thus, we reformulate the problem instead as minimization over \(v_t\), which gives the following:

Find \(v\colon [0,1]\to \mathfrak{X}(M)\) that minimizes

\begin{equation}\label{eq:shape_energy} E(v) = \int_0^1 \langle v_t,A v_t\rangle_{L^2} \, dt + \frac{1}{\sigma^2} d_S(\gamma(1)\cdot s_0, s_1)^2 \end{equation}

where \(\gamma(1)\) is determined from \(v\) via

\begin{equation}\label{eq:reconstruction} \dot\gamma(t) = v_t\circ\gamma(t), \quad \gamma(0) = \operatorname{id} . \end{equation}

This is the geodesic shape matching problem.

Governing partial differential equations

Thus far we have formulated the basic matching problem in shape analysis, but we have not yet solved it. More precisely, to “solve it” means two things. First, to solve the mathematical problem, i.e., prove that it has a solution. Second, to find an algorithm that can be used to compute a numerical (approximative) solution. Of course, the two go hand-in-hand and are both essential parts of shape analysis.

Existence (but not uniqueness) of solutions to the geodesic shape matching problem can be established by a variant of the direct method in calculus of variations. There are quite a few technical details in the proof, so I’m not going to repeat it here. An excellent exposition is given in the monograph on shape analysis by Younes

An alternative to the direct method is to work out the governing differential equations via the Euler-Lagrange equations and then try to analyze those equations. The first observation is that \(\gamma(t)\) must be a geodesic curve on \(G\). Why? Because the second term in the matching energy \eqref{eq:shape_energy} depends only on the end-point \(\gamma(1)\). Consequently, if \(\gamma(t)\) is a curve that extremizes the energy functional \(E\) for variations that vanish only at the initial point \(\gamma(0)=\operatorname{id}\), it must also extremize the functional for variations that vanish both at the initial and end points. Viewed differently, the geodesic shape matching problem consists of finding a minimizing geodesic \(\gamma(t)\) on \(G\) with \(\gamma(0)=\operatorname{id}\) and initial velocity \(\dot\gamma(0)\) chosen so that \(d_S(\gamma(t)\cdot s_0, s_1)\) is minimized (it’s a shooting problem).

To obtain the geodesic equation on \(G\), we first need to understand how variations of \(\gamma\) propagate to variations in \(v\). For a variation \(\tilde\gamma_\epsilon\) of \(\gamma\) we have a corresponding variation \(\tilde v_{\epsilon}\) of \(v\), defined by

\[\tilde v_{\epsilon}\circ \tilde\gamma_\epsilon = \dot{\tilde\gamma}_\epsilon .\]If we differentiate this relation with respect to \(\epsilon\) we obtain, using the chain rule, that

\[(\delta\tilde v_{\epsilon} ) \circ \gamma + (\nabla v)\circ \gamma \cdot \delta\tilde\gamma_\epsilon = \delta\dot{\tilde\gamma}_\epsilon\]where \(\delta\) denotes differentiation with respect to \(\epsilon\) at \(\epsilon = 0\), i.e., \(\delta = \frac{d}{d\epsilon}\big|_{\epsilon=0}\). Thus, \(\tilde v_\epsilon\) fulfills

\begin{equation}\label{eq:v-variation} \delta\tilde v_\epsilon = \delta\dot{\tilde\gamma} \circ \gamma^{-1} - \nabla v\cdot (\delta\tilde\gamma_\epsilon\circ\gamma^{-1}) . \end{equation}

The quantity \(u \equiv \delta\tilde\gamma_\epsilon\circ\gamma^{-1}\) is a mapping \((t,x)\mapsto u(t,x) \in T_x M\). In other words, \(u\) is a time-dependent vector field on \(M\). From its definition we see that its time derivative fulfills

\[\delta\dot{\tilde\gamma}_\epsilon = \dot u \circ\gamma + (\nabla u)\circ\gamma \cdot \dot\gamma .\]Compose this expression with \(\gamma^{-1}\) and plug-in the result in \eqref{eq:v-variation} to obtain

\begin{equation}\label{eq:v-variation-final} \delta\tilde v_\epsilon = \dot u + \nabla u\cdot v - \nabla v\cdot u . \end{equation}

It’s getting interesting! The pairing of \(\nabla v\) with \(u\) is exactly the co-variant derivative of \(v\) along \(u\) (and vice versa), from now on denoted \(\nabla_u v \equiv \nabla v\cdot u\). So the last two terms in \eqref{eq:v-variation-final} constitute the Jacobi-Lie bracket, which, as we saw above, is the Lie bracket for the Lie algebra \(\mathfrak{X}(M)\) of \(\operatorname{Diff}(M)\). That variations of \(v\) take this form is certainly not a coincidence: it reflect the general form of variations in Euler-Poincaré equations (cf. Marsden and Ratiu

We are now ready to compute the variation of the action functional

\[S(\gamma) = \frac{1}{2}\int_0^1 \int_M v \cdot Av \, dx \, dt\]for geodesics on \(G\). Indeed,

\[\delta S(\tilde \gamma_\epsilon) = \int_0^1 \int_M \delta \tilde{v}_{\epsilon,t} \cdot Av \, dx \, dt\]which combined with \eqref{eq:v-variation-final} yields

\[\delta S(\tilde \gamma_\epsilon) = \int_0^1 \int_M (\dot u + \nabla_v u - \nabla_u v) \cdot Av \, dx \, dt .\]Now we need to isolate \(u\) to get (think of \(u\) as the generator for the variation of \(\gamma\)). Integration by parts is our friend here. First, with respect to time, using that \(u(0,\cdot) = u(1,\cdot) = 0\), so the boundary terms vanish

\[\delta S(\tilde \gamma_\epsilon) = \int_0^1 \int_M \Big[ (\nabla_v u - \nabla_u v) \cdot Av - u\cdot \frac{d}{dt}Av \Big] dx \, dt\]which can also be written

\[\delta S(\tilde \gamma_\epsilon) = \int_0^1 \Big[ \langle \nabla_v u - \nabla_u v, Av \rangle_{L^2} - \langle u , \frac{d}{dt}Av \rangle_{L^2} \Big] dt.\]Next, we need to compute the adjoint of the linear operators \(u\mapsto \nabla_v u\) and \(u\mapsto \nabla_u v\). It takes some effort on a general manifold, but in our case, for the flat torus \(M=\mathbb{R}^n/\mathbb{Z}^n\), the coordinate variables \(x^i\) can be handled independently which makes it much easier. For the first operator

\[\langle \nabla_v u, w \rangle_{L^2} = \int_{M} \sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^n \frac{\partial u^i}{\partial x^j} v^j w^i = \int_{M} \sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^n u^i \frac{\partial}{\partial x^j}(-v^j w^i)\] \[= \int_{M} \sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^n u^i \Big(-\frac{\partial v^j}{\partial x^j} w^i - v^j\frac{\partial w^i}{\partial x^j} \Big) = \langle u, -\nabla_v w - \operatorname{div}(v)w\rangle_{L^2}\]Thus, the adjoint is given by \(-\nabla_v w - \operatorname{div}(v)w\). (This formula is valid also for a general manifold). The second operator \(u\mapsto \nabla_u v\) doesn’t take any derivatives of \(u\), so computing its adjoint is more a question of index bookkeeping:

\[\langle \nabla_u v, w \rangle_{L^2} = \int_{M} \sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^n \frac{\partial v^i}{\partial x^j} u^j w^i\] \[= \sum_{j=1}^n \sum_{i=1}^n u^j \frac{\partial v^i}{\partial x^j} w^i = \langle u, \nabla v^\top w \rangle_{L^2} .\]Using these results for the adjoints we obtain

\[\delta S(\tilde \gamma_\epsilon) = \int_0^1 \langle u, -\nabla_v Av - \operatorname{div}(v)Av - \nabla v^\top Av - \frac{d}{dt}Av \rangle_{L^2} \, dt.\]The curve \(\gamma(t)\) is a geodesic if and only if \(\delta S(\tilde\gamma_\epsilon)=0\) for all admissible variations, i.e., for all time-dependent vector fields \(u\) vanishing at the end points. As seen in the last calculation, the necessary and sufficient condition is that the variable \(m\equiv Av\) (called momentum in mechanics) fulfills the following partial differential equation

\begin{equation} \label{eq:epdiff} \dot m + \nabla_v m + \operatorname{div}(v)m + \nabla v^\top m = 0, \quad m =A v \, . \end{equation}

This equation is the one Mumford derived in the proceedings mentioned above

We are now ready to give the “shooting formulation” of the geodesic shape matching problem:

Find initial conditions \(m_0\in \mathfrak{X}(M)\) for equation \eqref{eq:epdiff} that minimize the energy

\begin{equation}\label{eq:shooting_form} E(m_0) = \langle m_0 , A^{-1}m_0 \rangle + d_S(\gamma(1)\cdot s_0, s_1)^2 \end{equation}

That the first term in \(E(m_0)\) is so simple follows from equation \eqref{eq:energy_from_initial} above. The second term, on the other hand, is complicated. Indeed, to evaluate it we need to

-

solve the EPDiff equation \eqref{eq:epdiff} for \(t\in [0,1]\) with initial conditions \(m_0\);

-

solve equation \eqref{eq:reconstruction} to obtain \(\gamma(t)\);

-

then, finally, compute the distance \(d_S(\gamma(1)\cdot s_0, s_1)^2\).

Numerical discretization (rough sketch)

I’ve given you (more or less) a complete mathematical description of shape analysis in its most simple setting. To be useful in applications, however, you also need to discretize the equations so that they can be used in the computer on real data. The theory of how to numerically discretize differential equations is a huge field – much larger than shape analysis. I’m not going to give a detailed account of how we discretize the geodesic shape matching problem. On the larger scale, however, there are two different approaches, and these two exactly match the two different types of analysis just presented: the direct method and the shooting formulation.

The formulation in equation \eqref{eq:shape_energy}, pertinent to the direct method in calculus of variations, suggests the following numerical method:

Replace the time-dependent vector field \(v_t\) with a sequence of vector fields \(v_1,\ldots,v_k\) and replace the energy functional \eqref{eq:shape_energy} by the corresponding Riemann sum

\[E(v_1,\ldots, v_k) = \frac{1}{k}\sum_{i=1}^k \langle v_i,A v_i \rangle_{L^2} + \frac{1}{\sigma^2} d_S(\gamma_k \cdot s_0, s_1)^2\]where \(\gamma_k\cdot s_0\) is obtained from \(v_1,\ldots,v_k\) by some numerical integration algorithm (for example a Runge-Kutta method). Start with \(v_i^{(0)} = 0\), then minimize the energy functional \(E(v_1,\ldots,v_k)\) with the gradient decent method:

\[v_i^{(j+1)} = v_i^{(j)} - \frac{\partial E}{\partial v_i}(v_1^{(j)},\ldots, v_k^{(j)})\]Of course, this also requires a spatial discretization of the space of vector fields, for example using the finite difference method or the finite element method.

The other numerical approach is based on the shooting formulation in equation \eqref{eq:shooting_form}. It requires a numerical time-stepping algorithm for solving the EPDiff equation \eqref{eq:epdiff} as an initial value problem. Thus, each initial momentum \(m_0\) gives rise to a corresponding discretized path \(\gamma_1,\ldots,\gamma_k\). This is where the warped mesh from above come back into the picure. Indeed, the way we discretize a diffeomorphism is to think of it as a deformed mesh, whose nodes move (in discrete time) according to the vector fields \(v_1,\ldots,v_k\). If the template \(s_0\) is a function, we can now evaluate the deformed function \(s_0\circ\gamma_k^{-1}\) at the regular mesh nodes by evaluating \(s_0\) at the corresponding deformed mesh nodes. To obtain the optimal, we again use the gradient descent method, but now over the (discretized) momentum variable \(m_0\) for the energy functional \(E(m_0)\) in equation \eqref{eq:shooting_form}.

Summary

We’ve seen in this post how the mathematical theory of shape analysis came about and how it looks like in the simplest case. There is, of course, a lot more to know about this field. Look out for future posts! ![]()

In the meantime, the papers by Beg et al

There is also a different viewpoint on shape analysis, which directly looks at infinite-dimensional manifolds of embedded submanifolds without going through diffeomorphisms; see these lecture notes by Mumford or, for more details and comparison between the two approaches, see the papers by Micheli et al

I should also stress that what you’ve seen in this post only reflect the single matching problem, with one template and one target shape. Ultimatelly, we would like to do statistics on shapes (this is indeed Grenander’s motivation). Many people have worked in this area, but I didn’t review any of their work here; think of the post you’ve read as an entry-point to more advanced subjects within shape analysis. A cool example: Stefan Sommer constructs random walks in shape space!